A Easy Drawing of the White House

The White House Collection

-

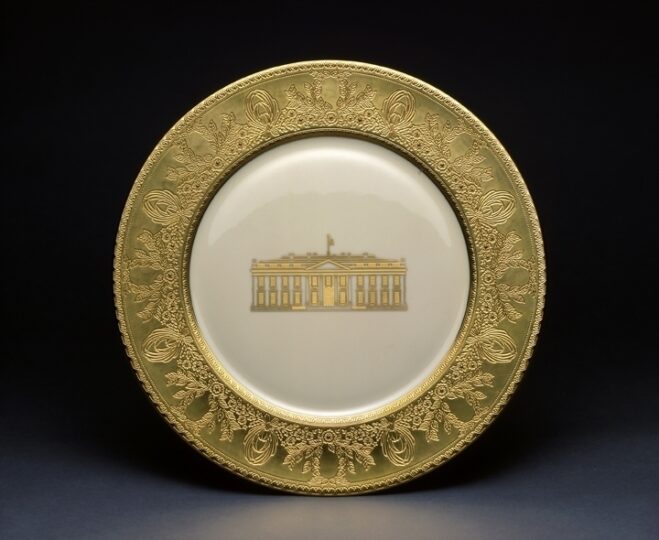

![200th Anniversary China: Plates]()

Dinner plate, luncheon/fish plate, for 200th Anniversary China manufactured by Lenox. Debuted November 9, 2000.

Gift of White House Acquisition Trust

-

!["View of Lake George"]()

View of Lake George, c. 1850-1860, attributed to Andrew Andrews

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1975.

-

!["Sailing off the Coast"]()

Sailing off the Coast, 1869, by Martin Johnson Heade

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1980.

-

![200th Anniversary China: Service Plate]()

Service Plate Design, for 200th Anniversary China manufactured by Lenox. Debuted November 9, 2000.

Gift of White House Acquisition Trust

-

![Armchair]()

Armchair, c. 1793-97

A gift of Mr. and Mrs. Shepley Evans and the White House Historical Association, 1975.

-

![Chinese Tea Box]()

Chinese tea box, c. 1811. The pink-ground French wallpaper lining is believed to have been installed in the White House before the 1814 fire.

White House Acquisition Fund, 1971

-

![Cylinder Desk]()

Cylinder Desk with a bookcase, crafted c. 1830

Gift of the White House Acquisition Trust in 2000

-

![French Porcelain Vases]()

Two French porcelain vases with the painted images of George Washington and John Adams, c. 1820.

Gift of the White House Historical Association in 2000

-

![Goblet]()

Goblet, c. 1840-60

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1993

-

![Rug Design]()

Rug Design, Bolletin and Thompson for Tiffany studios, 1926

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1995

-

![Sofa Table]()

Sofa Table, c. 1805-10

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1975

-

![Tall Case Clock]()

Tall case clock, c. 1795-1805

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1972

-

![William Howard Taft Etching]()

William Howard Taft, 1911, etching by Anders L. Zorn

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1989

-

![Treasures of the White House: "Resolute" Desk]()

880.177. 1

This double pedestal partners' desk, usually called the "Resolute desk", was made from the oak timbers of the British ship H.M.S. Resolute as a gift to President Rutherford B. Hayes from Queen Victoria in 1880. It has been used by every president since Hayes, excepting Presidents Johnson, Nixon, and Ford, 1964-1977.

It was used in the President's Office on the Second Floor of the Residence from 1880 until 1902, at which time the office was moved to the newly constructed West Wing. This desk remained, however, on the Second Floor of the Residence in the President's Study. President Franklin D. Roosevelt requested that the rear kneehole be fitted with a panel carved with the presidential coat-of-arms, but he did not live to see it installed in 1945.

After the Truman Renovation of the White House, 1948-1952, it was placed in the Broadcast Room on the Ground Floor where it was used by President Dwight D. Eisenhower during radio and television broadcasts. It was first used in the Oval Office in 1961 at the request of President John F. Kennedy. After President Lyndon B. Johnson selected another desk for his office, it was lent to a Kennedy Library traveling exhibition, 1964-1965, and then to the Smithsonian Institution for exhibition, 1966-1977.

In January 1977, President Jimmy Carter requested that this historic desk be returned to the White House for use again in the Oval Office. In 1981, President Ronald W. Reagan also chose to use this desk in the Oval Office. President George Bush used it in the Oval Office for five months in 1989 before having it moved to his Residence Office in exchange for a partner's desk which he had used in his West Wing office as Vice President. It was returned to the Oval Office for use by President Bill Clinton, 1993-2001. President George W. Bush has chosen to continue using it in the Oval Office.

A brass plaque affixed to the desk records the history of its creation:

"H.M.S. 'Resolute', forming part of the expedition sent in search of Sir John Franklin in 1852, was abandoned in Latitude 74º 41' N. Longitude 101º 22' W. on 15th May 1854. She was discovered and extricated in September 1855, in Latitude 67º N. by Captain Buddington of the United States Whaler 'George Henry'. The ship was purchased, fitted out and sent to England, as a gift to Her Majesty Queen Victoria by the President and People of the United States, as a token of goodwill & friendship. This table was made from her timbers when she was broken up, and is presented by the Queen of Great Britain & Ireland, to the President of the United States, as a memorial of the courtesy and loving kindness which dictated the offer of the gift of the "Resolute'."

Office of the Curator, The White House

Gift of Queen Victoria, 1880

-

![Treasures of the White House: Abraham Lincoln]()

Signed and dated lower left: G.P.A. Healy / 1869

939.1388.1

Lincoln's last public address was delivered on April 11, 1865, from a window above the north door of the White House, two days after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House. His subject-was national reconciliation and the reconstruction of the South, and he concluded: "I am considering, and shall not fail to act, when satisfied that action will be proper." With his death just days later all action was ended, but in this portrait he is still considering, and he seems to attend to other voices.

Healy had begun work on a portrait of Abraham Lincoln for which the President had sat in August 1864. The assassination, however, turned the artist's thoughts in another direction, and he conceived The Peacemakers, the small version of which was completed late in 1868. In The Peacemakers Lincoln leans forward, listening attentively to General Sherman's urgings, as he habitually did to the advice of his counselors before offering his own pondered decisions. In the 1869 portrait Healy had the artistic inspiration of his career. He made the decision, no less pondered, to remove the president from all human assembly while preserving the listening, absorbed pose.

The portrait was painted in Paris and sent to Washington in response to an act of Congress (March 3, 1869) authorizing a Lincoln portrait for the White House. When President Grant chose another likeness by William Cogswell, Lincoln's son Robert Todd Lincoln purchased the Healy, later declaring that "1 have never seen a portrait of my father which is to be compared with it in any way."

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

Bequest of Mrs. Robert Todd Lincoln, 1939

-

![Treasures of the White House: Adams' Tea or Coffee Urn]()

This Sheffield silverplate urn, made in England, circa 1785-88, was once owned by John and Abigail Adams, the first occupant of the President's House in 1800. This neoclassical vase-shaped urn, a type popular in England circa 1770-1800, was possibly acquired when Adams was American minister to England (1785-88). The front is engraved with the cypher "JAA" in a form found on some family silver documented in the inventory taken at Adams' death in 1826. It descended in the Adams family until it was sold in 1946.

Office of the Curator, The White House

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Mark Bortman and Jane Bortman Larus, 1964

-

![Treasures of the White House: Angelica Singleton Van Buren]()

Signed and dated, vertically at left edge on balustrade: H. Inman. I 1842.

890.2061.1

Martin Van Buren, eighth President, had been a widower for 18 years when he moved into the Executive Mansion in 1837. He was never to remarry, so the Van Buren White House lacked a hostess until that role was filled in 1839 by Angelica Singleton Van Buren (1817–1878). She was a native of South Carolina, the daughter of a wealthy and well-connected cotton planter and a relative by marriage of Dolley Madison, social doyenne of the capital. It was through Mrs. Madison that she met Van Buren's son and private secretary, Abraham, at the White House. They were married in November 1838, and on New Year's Day 1839 Angelica became the president's official hostess.

Inman displays artistic diplomacy in his treatment of the marble bust of Martin Van Buren on the right. Tricks of perspective make the sculpture appear to be farther back in the picture space than in fact is logical. Inman reduces the sculpture's actual size as well, so it does not compete with the head of Angelica. At the same time he strongly–and arbitrarily–spotlights it, thus ensuring that the president will not fade into insignificance.

Inman's Angelica is so winning in her frank expression and her womanly warmth that a dominant trait of her personality is quite obscured–hauteur. She and her husband had gone in the spring of 1839 to Europe, as ambassadors-without-portfolio. Angelica had been mightily impressed with the customs at the courts of Queen Victoria and Louis Philippe, where queens and even bourgeois "princesses" did not stand in receiving lines and shake the hands of the citizenry, the custom at the White House. Rather, they stood on platforms and received the homage of their subjects. Angelica briefly introduced the practice at the White House. When a Whig congressman branded her a "Democratic peacock in full court costume, strutting," she abandoned the attempt. Despite the elegance of her costume in this portrait, the vital, accessible human being of Inman's vision is Angelica Van Buren to all who have seen it.

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

Bequest of Travis C. Van Buren, 1890

-

![Treasures of the White House: Avenue in the Rain]()

Signed and dated lower left: Childe Hassam / February 1917

Inscribed on reverse, lower center: C. H. [circled] / February 1917

963.422.1

Hassam was the most prominent of the "Ten American Painters," a group founded in 1898 and influenced by recent French art. In his native Boston he had worked as a wood engraver of book illustrations before beginning to paint. Study in France in the late 1880s had introduced him to the Impressionists, whose broken brushwork and high-toned palette he emulated. Regarded as the leading American Impressionist, Hassam actually disliked the term and was stylistically conservative, with a tendency toward the chic in figure type and costume. Sociable and generous, he led a charmed professional life, achieving both fame and financial success.

The Avenue in the Rain was painted at the height of Hassam's powers, and is one of some 30 related paintings of flag-decorated streets that the artist produced between 1916 and 1919, during and immediately after the First World War. That they are intensely patriotic works is patent, while aesthetically they bear witness to the example of Claude Monet, both in the subject (Monet created two paintings of flag-bedecked avenues on a single day in 1878) and in the concept (a series of paintings of a motif, such as haystacks or Rouen Cathedral).

Hassam had long painted city views, and the ones in the flag series represent the climax of his career. The avenue is Fifth Avenue, frequently decorated with flags as American sentiment moved inexorably from isolationism toward intervention. The artist's most striking device here is the projection of flags into the picture from unseen points of anchor beyond the frame, covering a quarter of the surface of the painting. In one sense the flags become the surface of the painting, an identity seconded by the tall "hanging" format, which echoes a flag's shape.

Painted in February 1917, this work may have had a specific impetus: On January 22 President Wilson had delivered his "Peace Without Victory" address, holding out the ideal of a compromise peace that would leave no residue of bitterness. But sentiment to enter the war had been building since the May 1915 sinking of the British liner Lusitania by a German submarine. When the German government announced on January 31, 1917, that unrestricted submarine warfare would resume, the president broke off diplomatic relations. Three weeks later a German diplomatic note to Mexico proposing an alliance against the United States was intercepted, and Wilson sought congressional approval to arm American merchant ships. Although a declaration of war was still five weeks away, the turning point had been reached. Patriotic fervor peaked. It is reflected in The Avenue in the Rain, which ultimately is not a street scene, not a painting of flags, but in essence a vibrant flag unto itself.

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

Gift of T. M. Evans, 1963

-

![Treasures of the White House: Cabinet Room Conference Table]()

869.209.l

This walnut conference table was purchased for the Cabinet Room (then on the Second Floor of the White House) in 1869 during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant. It was part of a suite of furniture made by the Pottier & Stymus Manufacturing Co., a New York firm known for its high-quality product uniquely designed for each commission.

An interesting feature of the table are the locking drawers in which the President and his seven Cabinet officers (State, Treasury, War, Justice, Post Office, Navy, and Interior) could keep their papers. It is uncertain how an eighth Cabinet member was accommodated with the creation of the Department of Agriculture in 1889, but the table continued in use until 1902, when a new Cabinet Room was provided in the newly constructed West Wing.

In 1961, Mrs. Kennedy retrieved the remaining pieces from the suite - this table, a sofa, and four chairs - and returned them to the Second Floor room which had served as the Cabinet Room from 1865 to 1902, naming it the Treaty Room in honor of the many documents which had been signed there.

The historic documents which have been signed on this table include:

1. The Peace Protocol ending hostilities of the Spanish-American War, August 12, 1898, witnessed by President William McKinley in the Cabinet Room.

2. The Pact of Paris (Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact), 1929, signed by President Calvin Coolidge in the East Room.

3. Arms and nuclear testing treaties with the Soviet Union signed in the East Room by Presidents Nixon (1972), Ford (1976), Reagan (1987), and (Bush) 1990

4. Treaties with former Soviet republics (Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan), 1992, signed by President George Bush in the East Room

5. Middle East peace documents: Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty, 1979, on the North Lawn, witnessed by President Jimmy Carter, The Israel-Palestinian Declaration of Principles, 1993, on the South Lawn, hosted by President Bill Clinton, The Washington Declaration, Jordan and Israel, 1994, on the South Lawn, witnessed by President Clinton, West Bank Agreement, Israel and the Palestinians, 1995, in the East Room witnessed by President Clinton, Interim Accord, Israel and the Palestinians, 1998, in the East Room.

Office of the Curator, The White House

U.S. Government purchase, 1869

-

![Treasures of the White House: Dolley Madison]()

994.1737.1

This handsome portrait was painted by the celebrated artist, Gilbert Stuart, during his stay in Washington, 1803-1805. The great demand for the artist during this visit prompted a friend of Dolley Madison's to report that "Stuart is all the rage. He is almost worked to death, and everyone afraid they will be the last to be finished."

Dolley Madison, portrayed with her hair arranged in a neoclassical style and wearing a fashionable high-waisted Empire-style dress, was the popular wife of James Madison, then Secretary of State under President Thomas Jefferson. She often served as hostess at the White House for the widowed President.

In a letter to her sister, Anna Cutts, who was also painted by Stuart in 1804, Dolley Madison wrote, "Steward has taken an admirable picture of Mr. Madison - his and mine are finished." James Madison commissioned the portrait of his wife along with a companion likeness of himself for the Madison's Virginia home, Montpelier. They hung in the drawing room of their home until after James Madison's death in 1836. The pair of portraits later hung in her home on Lafayette Park in Washington, D.C.

Following Mrs. Madison's death in 1849, the Madison portraits became the property of her son, Payne Todd. They were sold at auction in Washington. D.C., in March 1851, along with many of her other possessions. Anna Payne Causten, Mrs. Madison's niece, and her husband purchased the portrait of Dolley Madison. Following their deaths, the painting was left to their daughter, Mary Causten Kunkel. It was sold at auction in Philadelphia, on May 9, 1899, by Mrs. Kunkel and acquired by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In 1970, the Academy lent the portrait of Mrs. Madison to the White House. It was acquired for the White House collection in 1994.

Source: Office of the Curator, The White House

Gift of the Walter H. and Phyllis J. Shorenstein Foundation in memory of Phyllis J. Shorenstein, 1994

-

![Treasures of the White House: East Room Chandelier]()

902.3057.1

For the 1902 Theodore Roosevelt renovation of the White House, the architects McKim, Mead & White commissioned the noted New York firm Edward F. Caldwell & Co. to provide lighting fixtures. In the East Room were hung three massive electric chandeliers made of cut glass and gilded brass by Christoph Palme & Co., Parchen, Bohemia (Austria-Hungary). Only a year later the chandeliers were taken down and "the diameter of the lower portion reduced in size". They were shortened and modified again during the Truman Renovation (1948-1952). Each chandelier currently consists of about 6000 pieces of glass and weighs about 1200 lbs.

Office of the Curator, The White House

U.S. Government purchase, 1902

-

![Treasures of the White House: George Washington]()

800.1290.1

On the afternoon of August 24, 1814, Dolley Madison received word at the White House from her husband the president that the British were about to march on Washington. He urged her to leave quickly. The British troops set fire to the Capitol Building that evening, then a naval contingent moved on to the White House. While the naval officers ate the dinner that had been laid out for the Madisons, the sailors explored the house. After piling up the furnishings, they set them ablaze. The President's House was reduced to a shell, its contents consumed by the fire.

But Mrs. Madison had been determined that, in addition to official papers, the full-length portrait of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart must be kept from British hands. There was no time to unscrew it from the wall, so the frame was broken and the canvas on its stretcher carried from the house into the safety of the countryside. Not until 1817 was it returned to the rebuilt White House.

Although others had painted George Washington as military hero, it remained for Gilbert Stuart to create the authoritative image of the first president. No other portrait so conveys the unyielding resolve and severe dignity that made him the embodiment of the young Republic. Washington grasps a sheathed sword, emblematic of his military past and his present position as Commander in Chief. His civilian clothes remind us that after the peace was achieved in 1783 and the army disbanded, he had resigned his commission. This renunciation of power was so novel that it astonished Europeans as well as his own countrymen. A folio volume of the Constitution and Laws of the United States leans against (symbolically, supports) the table leg whose design joins elements of the fasces – the bound rods that symbolized authority and justice in the Roman republic–and the American eagle. Next to the Constitution is a history of the American Revolution. We know from another version of the portrait that the title of the book next to that one is Washington's General Orders, also recalling his military career. Likewise, the two books on the table are The Federalist and The Journal of Congress. These remind us of his steadfast support of the federal union and its Constitution.

The President's right arm is extended in one of the ancient Roman oratorical gestures, through which it echoes the ideals of the Roman republic. But the arm has been lowered and an imperious gesture modified by the contemporary English model of "conversation-piece" paintings in which men and women converse as equals.2 This is the man who had addressed Congress at his 1789 inaugural as "fellow-citizens."

Garry Wills, in Cincinnatus: George Washington and the Enlightenment, has deftly summarized most of the other symbolic elements in this painting:

Stuart's portrait derives from the grand manner style of court painting in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries; the artist borrowed freely from an engraving of a late 17th-century French portrait in composing this painting. But by introducing different objects and symbols and by substituting an attitude of plain speaking for one of aristocratic hauteur, Stuart changed the meaning of the borrowed forms.

Washington never posed for the standing figure. This was in accordance with standard portrait practice: The sitter posed for the head only, with perhaps some quickly drawn notations of the torso and the extremities, while the body was painted from a surrogate model or even invented. The White House portrait is probably' the last of four nearly identical versions painted by Stuart, though there is no unanimity on the order in which the portraits were created. Since one of the four was painted as a gift to the Englishman Lord Lansdowne, all four are commonly referred to as being of the "Lansdowne type." The head derives from a sitting in April 1796, requested specifically for use in painting the first full-length portrait.

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

United States Government purchase, 1800

-

![Treasures of the White House: Hayes State Dinner Service]()

880.3840.1

In 1879, a state dinner service for President and Mrs. Rutherford B. Hayes was commissioned from Haviland & Co., Limoges, France. After a meeting with Mrs. Hayes in the White House conservatory, Theodore R. Davis, an artist for Harper's Weekly, who advocated a service designed with American flora and fauna, was asked to assume direction of the designs. From his drawings, etchings were produced for transfer of the outlines to many new dish shapes; basic coloring was applied by chromolithographic and decalcomania processes and then shaded by decorators. The dinner platters (both extant) were described as painted with "a magnificent wild turkey, who struts through the light snow, upon which are seen delicate reflections from his rich-colored plumage...on this most perfectly American dish."

Some of the Hayes designs and forms were made for public sale as well, but on these the pennant mark dated 1879, unique to the White House service, was replaced by a blue 1880 patent mark.

Office of the Curator, The White House

U.S. Government purchase, 1880

-

![Treasures of the White House: Monroe Armchair]()

961.14.1

As part of the refurnishing of the White House after the fire of 1814, President James Monroe ordered for "the large oval room" (Blue Room) a suite of French mahogany furniture. The agents, Russell & LaFarge of Le Havre, however, substituted a suite of gilded beechwood furniture by the noted Parisian cabinetmaker, Pierre-Antoine Bellangé (1760-1844), asserting, that "mahogany is not generally admitted in the furniture of a saloon, even at private gentlemen's houses." The 53-piece was described on the 1817 shipping invoice as decorated with "olive branch ornaments, covered in double-warp satin, fine crimson".

In 1860, 28 chairs (perhaps what remained of the original 38) along with the original complement of sofas, stools, footstools, and screens were sold at auction in Washington, D.C. Only the pier table has remained continuously at the White House. Five armchairs, two side chairs, and one sofa have been returned to the White House since 1961. The two side chairs are the only pieces at the White House to bear traces of the maker's stamp. A group of reproductions (seven arm and four side chairs) was made in 1962 to supplement the three original chairs acquired in 1961-62.

Office of the Curator, The White House

Gift of Cathrine Bohlen, 1961

-

![Treasures of the White House: Lighter Relieving a Steamboat Aground]()

978.13392.1

This painting brings to life an era and a region in which storytelling was at once a way of life and an art form. Bingham was raised on the banks of the Missouri River near St. Louis, and he became its historian. He knew the river well, and as a young man he witnessed the change in its character as the flatboats that drifted with the current or were poled against it were supplanted by steamboats in the 1830s.

This is, as far as we know, the first painting in which Bingham depicted an accident on the river. The steamboat in the distance has run aground on a shoal, and this boat in distress probably alludes to a key political issue of the day. Obtaining federal funds to improve navigation and thus facilitate trade on the western rivers through the removal of snags, shoals, and sawyers was a primary goal of the Whig party in Missouri. In 1846 Bingham ran as a Whig for the Missouri House of Representatives. He was elected, but the results were contested. The Democrat-controlled legislature decided against him, and he was forced from office. Shortly afterward, to the fury of the Whigs, the Democratic President James K. Polk vetoed the River and Harbor Bill.

Although Bingham may indeed have had a political subtext in this painting, his primary focus is on the self-sufficient boatmen, his heroes. Having removed cargo from the steamer ("lightened" it so it can float free from the shoal), they have turned from it to listen to their storyteller. In the words of Henry David Thoreau, Bingham's contemporary, they are "building castles in the air for which earth offered no worthy foundation." Of this and another picture, a St. Louis reporter wrote that the artist has chosen "the simplest, most frequent and common occurrences on our rivers... precisely those in which the full and undisguised character of the boatmen is displayed."

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

Partial gift of an anonymous donor, 1978, and Mr. and Mrs. Walter Shorenstein, 1981

-

![Treasures of the White House: Monroe Plateau]()

817.3673.1

As part of the refurnishing of the White House after the fire of 1814, President James Monroe ordered for the dining room in 1817 a large gilded bronze plateau. Made in the large and prominent Parisian shop of Jean-François Denière and François Matelin (circa 1797-1820), it was described as "mat gilt with garlands of fruit and vines with figure of Bacchus and Bacchantes and pedestals on which are 16 Figures presenting wreathes for receiving lights [candles] and 16 cups for changing at will, composed of 7 pieces altogether 13 [sic 14] feet 6 inches long, over 2 feet wide, set with its mirrors." It was accompanied by three baskets, a pair of urns, and a pair of stands, all extant.. In 1854, 32 cut glass dishes were acquired as an alternative to candles.

Office of the Curator, The White House

White House Historical Association

-

![Treasures of the White House: Rocky Mountain Landscape]()

981.1468.1

When Albert Bierstadt painted Rocky Mountain Landscape in 1870, he had not seen the Rockies for seven years. He worked from studies made in 1863, during his second trip to the West. He had recently returned from a triumphal two-year tour of Europe; the following year he would go west again.

Bierstadt's dramatic sense was keen, and he was a master at the creative transformation of a few basic compositions. He adopted devices associated with the theater: The contrast of the darkened proscenium and wings with the light-struck sky and water enhances the scene. The eye moves into the space by diagonal steps, from the family of deer (the only animate objects in the painting) just right of center, to the stand of trees, to the right distance, and to the soaring cathedral rock across the water. Finally, the most distant snow-covered peaks are seen at top left center. Against this Bierstadt develops a curvilinear play in the cuplike curves of rocks and lakeshore. With the clarity and spatial penetration of a stereographic view (his use of photography is well documented), he rivets our gaze. The innumerable oil sketches from which he composed his large canvases are typified by the brisk cloud study reproduced above. It is alive with the exhilaration of on-the-spot observation.

In Rocky Mountain Landscape the shopworn adjectives "spellbinding" and "breathtaking" regain their identity, conveying the awestruck wonder the artist induces in the viewer. Both words imply the suspension of time. The cascades suggest neither sound nor motion; the great cloudbanks are stopped in their ascent; the still water of the lake mirrors the rocks and locks them to the foreground shore through the complex and beautiful pattern of reflections.

We dare not move lest we lose the waking dream. No humans are present except ourselves; we have stumbled upon a hidden valley. The disposition of light and shadow furthers this illusion. Around a core of light the artist has wrapped a dark cloak, sealing off this extraordinary place from the civilized world.

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

Gift of The Barra Foundation, Inc., 1981

-

![Treasures of the White House: Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City]()

995.1759.1

One of Henry Ossawa Tanner's largest and most artistically ambitious landscape paintings is this beautiful coastal view of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Depicted in the late afternoon light, windswept sand dunes appear before an ocean covered with a low haze that partially hides the sun. Upon close examination, one can see that the artist incorporated sand into the paint used to create the sand dunes.

Enticed by seasonal employment opportunities, Tanner visited Atlantic City many times during the summers of the 1870s and 1880s. Dewey F. Mosby in his biography of Tanner has suggested that this painting may originally have been entitled, Back from the Beach, and was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1885 and again at the National Academy in 1886.

Tanner, the son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister and a mother who conducted private school in her home, was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1859. At the age of twenty, he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and studied under Thomas Eakins and Thomas Hovenden. Although he spent over half of his life in France where he found an expansive and more accepting environment, he always considered himself an American. He made periodic visits to the United States and served as a lieutenant with the American Red Cross during World War I. On May 25, 1937, he died at his home in Paris.

This is the first work of art by an African-American artist to be part of the White House collection. Acquired from Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, grandniece of the artist, it was donated to the White House by the White House Endowment Fund.

Source: Office of the Curator, The White House

Gift of the White House Endowment Fund, 1995.

-

![Treasures of the White House: Seymour Tall Case Clock]()

972.919.1

The case of this clock, a form frequently made in New England, is an important example of the superb craftsmanship of father and son cabinetmakers John and Thomas Seymour of Boston, circa 1795-1805. Made of mahogany with crotch birch and satinwood veneers, the 8'lO" case also features a double lunette inlay that was a sophisticated Seymour ornament. Although its dial is unmarked, the movement may have been made by James Doull of Charlestown, Massachusetts, whose name appears on clocks with similar Seymour cases.

Acquired in 1972, this clock has stood in the Oval Office since 1975 and is one of the most beautiful clocks in the White House collection.

Office of the Curator, The White House

Gift of the White House Historical Association, 1972

-

![Detail, Steinway Piano]()

This photograph of the detail on the Steinway piano case was taken in the Entrance Hall on July 20, 2017 by Matthew D'Agostino. The mahogany concert grand piano with supporting eagles of gold leaf was presented to the White House by Steinway & Sons on December 10, 1938. The piano was designed by architect Eric Gugler who was also responsible for the 1934 expansion of the West Wing. The Entrance Hall is located on the State Floor of the White House.

White House Historical Association

-

![Treasures of the White House: The Lincoln Bed]()

861.60. 1

The massive rosewood bed known as the "Lincoln Bed" is believed to have been purchased by Mrs. Lincoln in 1861 for use in the principal guest bedroom of the White House. The popular reference to it as the "Lincoln bed" is derived not from its use by the Lincolns, but from its acquisition during their occupancy of the White House.

Measuring 8'4" long and 5'lO 1/2" wide, it has a very tall headboard, 93 1/4" high, featuring an oval center panel surmounted by an open, carved grapevine cresting on which are perched two exotic birds. A similar motif, with only one bird, is carved on the face of the much lower, arched footboard. Grape clusters, like those atop the pointed headboard stiles, are carved on the face of the rounded footposts.

An invoice dated May 29, 1861, from Wm H. Carryl and Bro., a Philadelphia retailer, includes, among other purchases for the White House, "1 Rosewood Bedstead" as part of a 10-piece suite of furniture costing $800. Also on this invoice was "1 Rich Rosewood Centre Table" which is believed to be an extant table similarly carved with grapevines and exotic birds.

An 1862 newspaper article quite fully describes this bed in its guest room setting:

The guests' room, now known as the Prince of Wales' room since that youth occupied it [Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, was received at the White House on October 4, 1860], has been thoroughly ornamented and refurnished... The principal feature of the room is the bed. It is eight feet wide and nine feet long, of solid rosewood. The sides are cushioned and covered with purple figured satin. The head board is a piece of rich carved work, rising eight feet above the bed, and having an oval top. Twenty feet above the floor, overspreading the whole, is a magnificent canopy, from the upper carved work of which the drapery hangs in elegant folds, being in the form of a crown, the front ornament upon which is the American shield with the Stars and Stripes carved thereon." (Daily Alta California, San Francisco, May 12, 1862).

Although the canopy with its patriotic shield ornamentation was certainly a special commission, it is unlikely that the bedstead itself was. Many examples of very similar beds are known to exist, some bearing makers' marks. This bed, however, is not marked in any way to indicate its manufacturer.

The bed was used in various Second Floor bedrooms, including those of President and Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, President Woodrow Wilson, and Grace Coolidge. In 1945, it was placed by President Truman in the room which had been Abraham Lincoln's office and cabinet room, which was then renamed the Lincoln Bedroom.

Office of the Curator, The White House

U.S. Government purchase, 1861

-

![Treasures of the White House: The Peacemakers]()

947.2558.1

The title is the only clue to the import of this solemn painting, a prelude to the end of the Civil War. Seated in the after cabin of the Union steamer River Queen are Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, President Abraham Lincoln, and Rear Adm. David D. Porter. Less than a week before the fall of Petersburg, Virginia, the four men met to discuss the nature of the peace terms to follow.

The events leading up to the scene recorded in The Peacemakers are these. Following his march through Georgia, Sherman with his army had turned to the Carolinas and, on March 19, 1865, had taken Goldsboro, North Carolina. Petersburg, the last defense of Richmond, where Gen. Robert E. Lee had gathered his forces, had been under siege by Grant's army for nine months. The end of the Civil War was at last imaginable.

On March 20 Grant invited Lincoln to visit him at his headquarters at City Point, on the James River near Richmond: "Can you not visit City Point for a day or two? I would like very much to see you and I think the rest would do you good."' Lincoln accepted this opportunity to relax while acquainting himself firsthand with the progress of the war. On March 24 he reached City Point on the River Queen. Sherman, according to his Memoirs, decided coincidentally to pay a visit to Grant at just this time, arriving on the evening of the 27th: "After I had been with him an hour or so, [Grant] remarked that the President [was on the River Queen]. . . and he proposed that we should call and see him."

Since Porter, in charge of the Union fleet on the James River, was also in City Point, he joined the others. On March 27 and again on the 28th, the four gathered aboard the steamer. The first meeting was, according to Sherman, "a good, long, social visit." During the second meeting their conversation, although wide-ranging, turned often to the conclusion of the peace. Only Sherman and Porter left written accounts, and some have suggested that they exaggerated Lincoln's desire for peace, as Porter put it, "on almost any terms" in order to justify Sherman's later, controversial liberal surrender terms to Gen. Joseph Johnston. But Lincoln's generous intentions had been memorably formulated in his Second Inaugural Address, just three weeks before: "With malice toward none; with charity for all."

Following the meeting shown in The Peacemakers and preceding the end of the war by one week, Petersburg fell on the night of April 2 after the long siege. Grant and Lincoln entered the city the next day. On his return to the Union base at City Point, Lincoln told Porter: "Thank God I have lived to see this. It seems to me that I have been dreaming a horrid dream for four years, and now the nightmare is gone. I want to see Richmond." Together they sailed upriver to the defenseless capital of the Confederacy. There Lincoln, less than a fortnight before his assassination, walked the streets amid a swelling throng of emancipated black people.

The Peacemakers documents in measured accents this turning point of American history. Its somber figures–less actors than audience–await the denouement, the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

United States Government purchase, 1947

-

![Treasures of the White House: Thomas Jefferson]()

962.395.1

This compelling likeness of Thomas Jefferson as Vice President, together with the artist's 1795 portrait head of George Washington (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), is the triumph of Peale's career. He painted both his early masterpieces before study in Paris in 1808–10, which denaturalized his fresh, direct vision and infected his style with a classicizing manner.

The portrait of Jefferson was completed in Philadelphia before mid-May 1800, when he left that capital for Monticello. An engraving of the portrait by Cornelius Tiebout was published on February 20, 1801, less than two weeks before Jefferson became the first President to be inaugurated in the new capital city of Washington. The engraving, widely circulated in the United States and abroad, became the public image of Jefferson the President (1801-09).

Again and again one reads of Jefferson's serenity; this portrait confirms it. As a presentation of the harmonious nature and balanced intellect of the man, it is unequaled. The face has the glow of health, a warm complexion that bespeaks a warm personality. In contrast to the subjects in many early presidential portraits, the sitter here looks directly at us and does so with candor, as our equal. The splendid eyes and mouth convey reason and tolerance. It is an inherently democratic picture and a fitting summation of the century just concluded, the Age of Enlightenment.

But it is equally an announcement of a new age in America's political life. During the John Adams Administration the deep rifts between the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans had taken a bitterly personal turn, and the animosity of the campaign of 1800 was intense. When the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, where it remained deadlocked for 35 ballots, civil war was spoken of. Jefferson's election on February 17, 1801, could not end the turmoil, but Jefferson himself could. It is an easy matter to match the face in this portrait with the sentiment expressed in Jefferson's first inaugural address on March 4, a reasoned and ungrudging reminder that every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle: "We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it."

Source: William Kloss, et. al., Art in the White House, New York: Abrams, 1992.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1962

-

!["Resurrection" in the Vermeil Room]()

Titled "Resurrection," this acrylic and graphite on canvas painting was done by Alma Thomas in 1966, who was an educator and artist in Washington, D.C. for most of her career. She was a member of the Washington Color School. This painting was unveiled as part of the White House Collection during Black History Month 2015 and is the first in this collection by an African American woman. This photograph shows the painting on display in the Vermeil Room, during a press preview of the White House holiday decorations on November 30, 2020. The holiday theme for 2020 was America the Beautiful, which celebrated the natural wonders of the American landscape. Selected by First Lady Melania Trump, the White House decorations also paid tribute to the courage and resilience of frontline workers, members of the military, and other American heroes. In 2020, American frontline and essential workers faced unique challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Matthew DAgostino for the White House Historical Association

mullawirraburkaheact1966.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.whitehousehistory.org/galleries/the-white-house-collection

0 Response to "A Easy Drawing of the White House"

Post a Comment